The Ninth Symphony – Beethoven & Béjart

Created in Vienna in honor of King Frederic William III of Prussia, the Ninth was composed between the end of 1822 and February 1824. A condensed version of paradoxes and excesses, Wagner said that it was “the last symphony”.

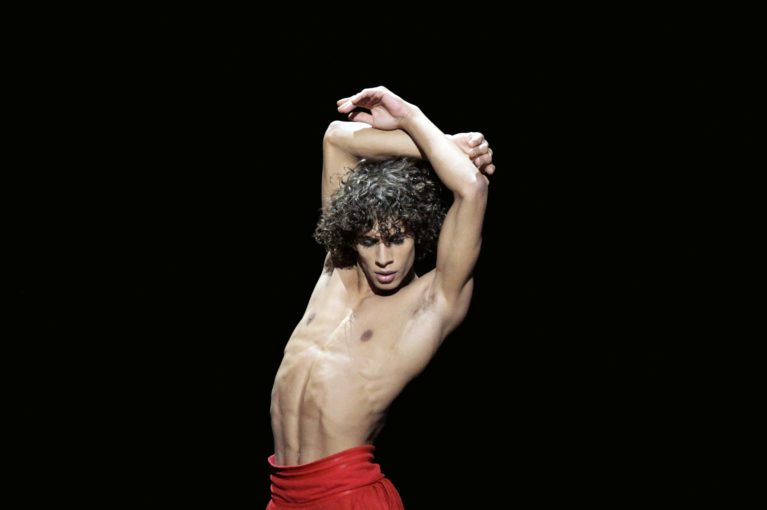

Choreographing the Ninth was an act of faith by Béjart to Schiller’s original message – a willingness to gather a collective and secular prayer in Beethoven’s spirit.

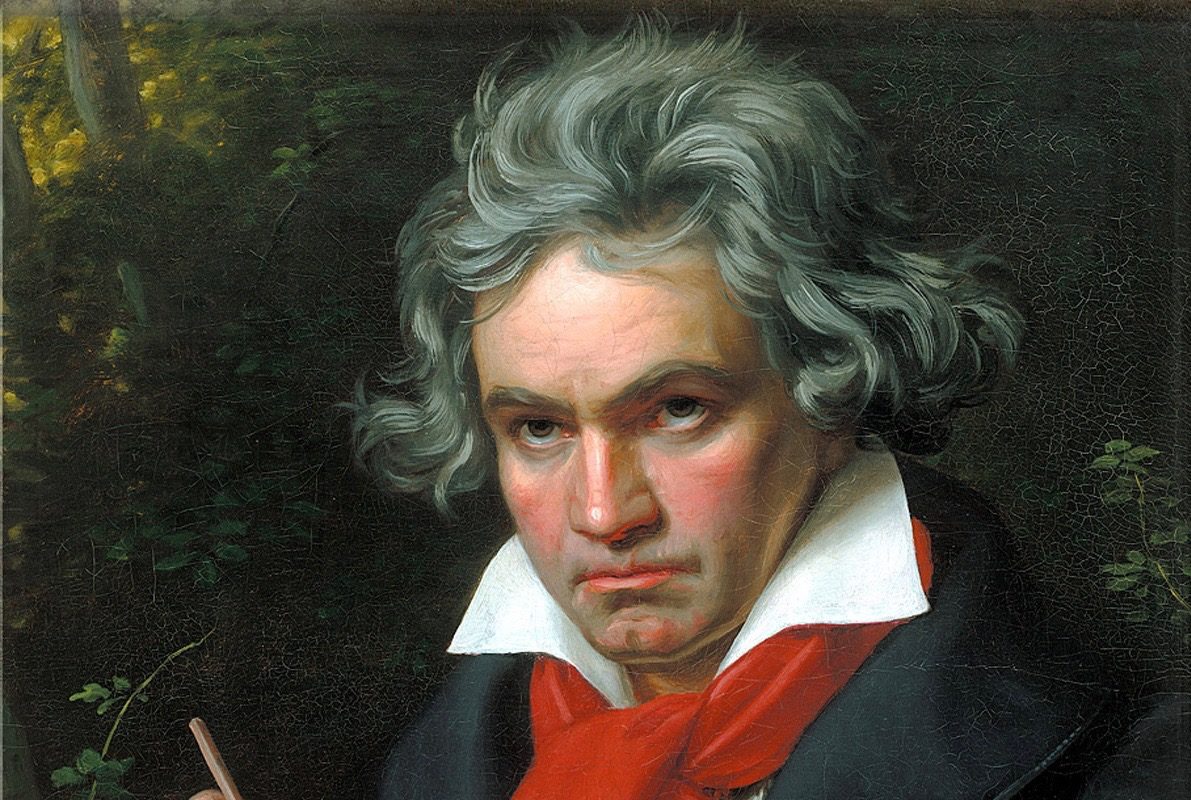

Like Beethoven, the Ninth Symphony is a condensed version of paradoxes and excesses. Let’s first consider its duration. The Ninth is more than an hour long, nearly half of which is devoted to the fourth movement where the choir and soloists join an orchestra already collapsing under the timbres of the strings, woodwinds, brass instruments and abundant percussions. The musical structure is constantly on the move, transitioning from fury to transparency, from triumphant affirmations to areas of shade and restraint. The composer plays around with codes and invents unusual paths amidst deliberately composed chaos. The progression of his symphony isn’t linear: it is contradictive, turbulent, and pugnacious. Various themes emerge and disappear, trapped on a gigantic revolving carousel, on the verge of disintegrating before picking up again. All this blaze the way for the voices. The songs are assertive and reveal a supreme solution.

A musical researcher

Beethoven was isolated, lonely, and suffered from being walled in complete deafness. This man had nothing to lose and let grandiosity explode and revolt itself in an overwhelming sound of fury calling for universal solidarity and love. He contributes his individuality and fascinating musical experiments in the field of sonata and string quartet to the collective good. Above all, he built a gigantic symphony which gave birth to an ode to disarming melodic simplicity. This will obviously continue to serve as a field of exploration, between variations, escapes and other recipes for the great master.

The project of a symphony with a choir had been in the making for years. Fantasy was played on the piano and the 1808 choir and orchestra set the tone, but in a more bucolic genre. In fact, Christophe Kuffner’s poem celebrated the beauty of sounds and harmonies. He recalls “the spring sun of the arts” was capable of “making peace and happiness shine through”. But Schiller’s humanist and political ideals were already carried by Beethoven for a long time. Beethoven had to endure the harsh political situation imposed on Vienna by Metternich and his police. Amidst a hostile environment to the ideals of the French Revolution, Beethoven put the Ode back on track in 1822 with the desire to make Schiller’s message accessible to the largest audience possible. Fiercely indifferent to the technical difficulties he imposed on the instrumentalists of the elitist field of chamber music, sweeping away or angering their dismayed comments at the sight of the scores to be played, convinced of the relevance of his aesthetic choices, whose arrangements were perfectly understood in his mind, Beethoven insisted that his Ninth would be for the people, much like his Missa Solemnis. His bet ended up being successful beyond his wildest expectations. His Ode to Joy however, was misused by many.

A disputed anthem

Few works have served so many masters. If Wagner made Woody Allen “want to invade Poland”, the Ninth galvanized Chancellor Bismarck, the architect of the German unification: “if I hear this music often, I always feel very brave”. During the nationalistic movements of the 19th century, the appearance of national anthems crystalized identity and therefore, exclusion. The Ode to Joy became an “Anthem” and Schiller and Beethoven were soon enrolled side by side… on either side of the trenches. “The Ode to Joy is an Allied anthem, the credo of all our hopes. The German thief should be prohibited from ever playing a single measure of it,” Camille Mauclair wrote in March 1927. From the very beginning, National Socialism did not fail to claim Beethoven’s work, Wagner’s “precursor”, although genealogy specialists could not agree on his case, concluding that he was a “Rasse gemischt” (mixed race). Indeed, it is hard to ignore the composer’s facial traits, his black eyes, his dark hair, his unsightly body, at the opposite of Aryan beauty standards.

A collective and secular prayer

The Fidelio opera was banned, but the Ode to Joy was played during the opening ceremony of the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games, during which Pierre de Coubertin, impressed by the parade, praised “the muscular agreements stronger than death itself.”As a hymn to the young gymnasts and the German people, their vision of human solidarity excluded sub-human races. The same was true in Rhodesia in 1974, when the Ode to Joy was declared as a national anthem at the height of the Apartheid regime. Meanwhile, in 1972, Herbert von Karajan came up with an edited version, shortened and simplified, which would serve as the European Anthem. Let’s also remember that Beethoven played in front of the Berlin Wall in 1989 or in Sarajevo in 1996.

The Ninth is miraculous bandage which should urgently be applied to all the wounds Humanity inflicts on itself. “All those who claimed to belong to the Ninth experienced its beauty first then moved on to the necessity of its morality”, Esteban Buch wrote at the end of his fascinating Beethoven’s Ninth: A Political History (ed. Gallimard, 1999). One might wonder: “are we ready to accept the idea that, someday, it may become mute without it necessarily being a disaster?”

Béjart wanted to see her dance. The Ninth in body language—a symphony of being in movement interacting with each other. An orchestration of individual and collective energies. The choreography is not a salvaged work, but an act of faith to Schiller’s original message. In Beethoven’s mind, it is a desire to bring together a collective and secular prayer, an ode to Humanity’s potential, not a hymn to its glory. Beethoven’s choreographed Ninth thus finds its place as a work of art to experience with our feet on the ground, in our reality and in any way we feel about it.

Dominique Rosset – L’Hebdo

The Ninth Symphony by Maurice Béjart will be in Tokyo and Lausanne in 2020

- From April 25 to 29 at the Bunka Kaikan in Tokyo

- From June 12 to 17 at the Vaudoise Arena in Lausanne-Malley