The Ninth Symphony – A little bit of history

The idea of a “danced concert” about solidarity and universal love was born in Maurice Béjart‘s mind in the early 1960s in Havana. Back in Brussels, the choreographer created The Ninth Symphony. In 2014, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of The Tokyo Ballet, his successor breathes new life into this masterpiece and echoes the poetic message of Schiller: all men are brothers.

Maurice Béjart was inspired by Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and in 1964, he created a piece which reflects his purest instincts and embodies the ideal of a universal brotherhood—somewhere between pre-68 premonitions and a flirt with the sacred sphere. Gil Roman rejuvenates this “danced concert”, fifty years after its creation

There’s a revolution in the air

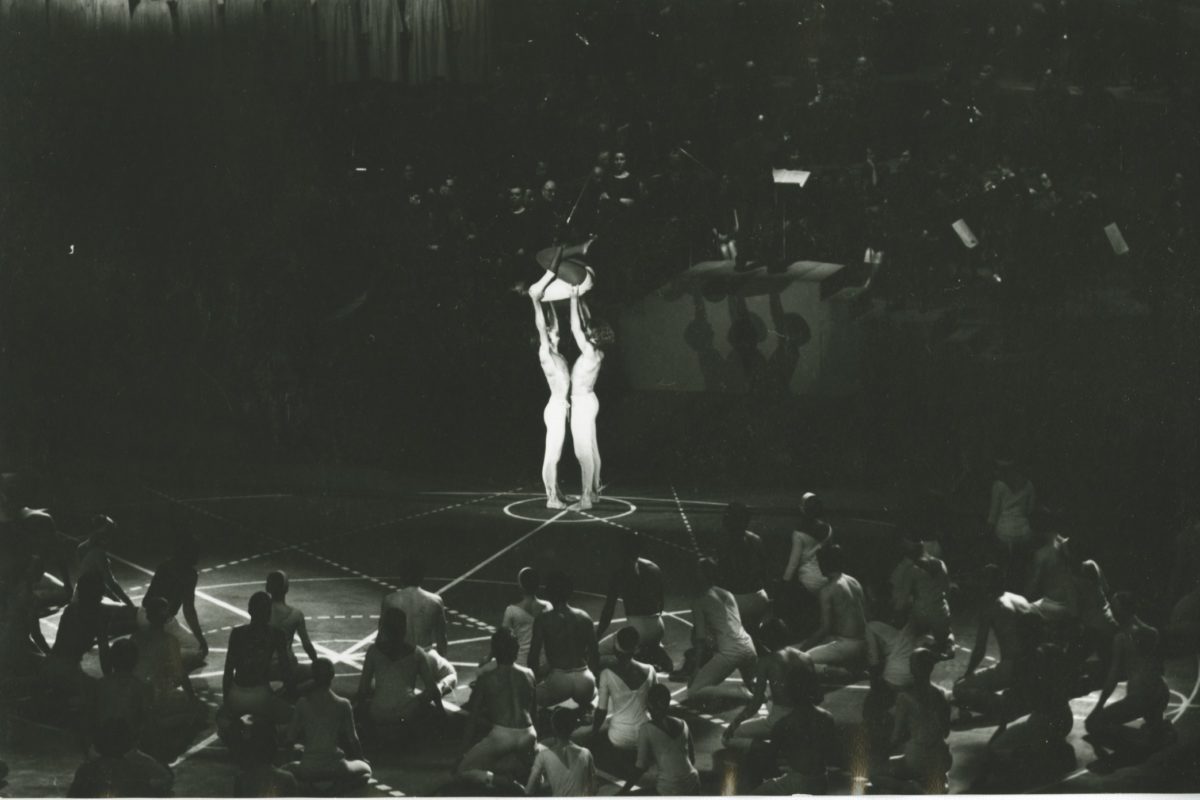

At the beginning of the 1960s, Maurice Béjart witnessed the performance of a young company of Cuban dancers in Havana. The fresh wind of the revolution was blowing through the streets, houses and theaters of the city. The ecstasy was tangible. Exhilarated by the performance, Béjart let himself get overwhelmed with the feeling of freedom and joy. As waves crash on the Malecón, an idea germinates, makes progress and takes shape in his mind. The desire to create grabs him. Yes, it will be a ballet. A symphonic ballet, “a danced concert”. He pictures ethnic groups coming from all horizons twirling on stage. A true experience of brotherhood and universal love. It was all there! Everything but the melody.

Back in Brussels, as he was talking about music with friends one evening, one of them jokingly said: “Why not the Ninth?” Instead of dismissing the idea, Maurice Béjart rushed to find the record. When Beethoven’s Adagio flooded the room, he truly heard it for the first time.

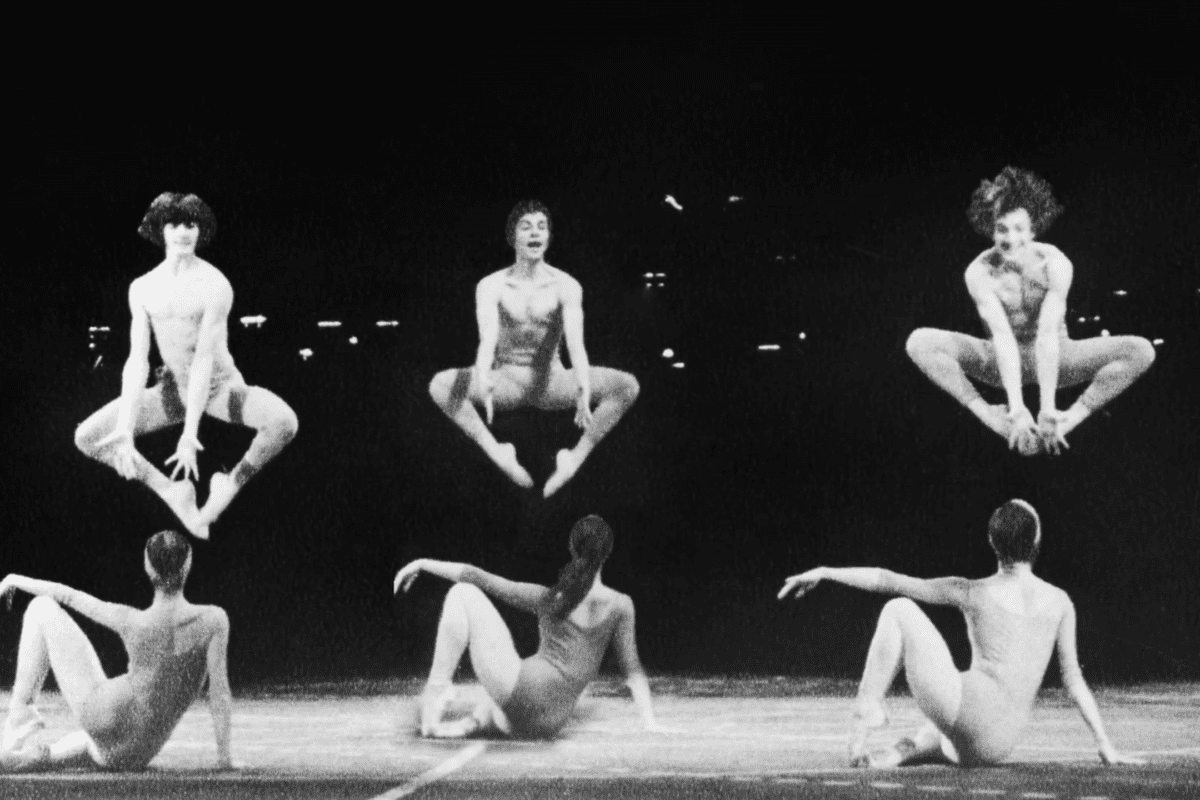

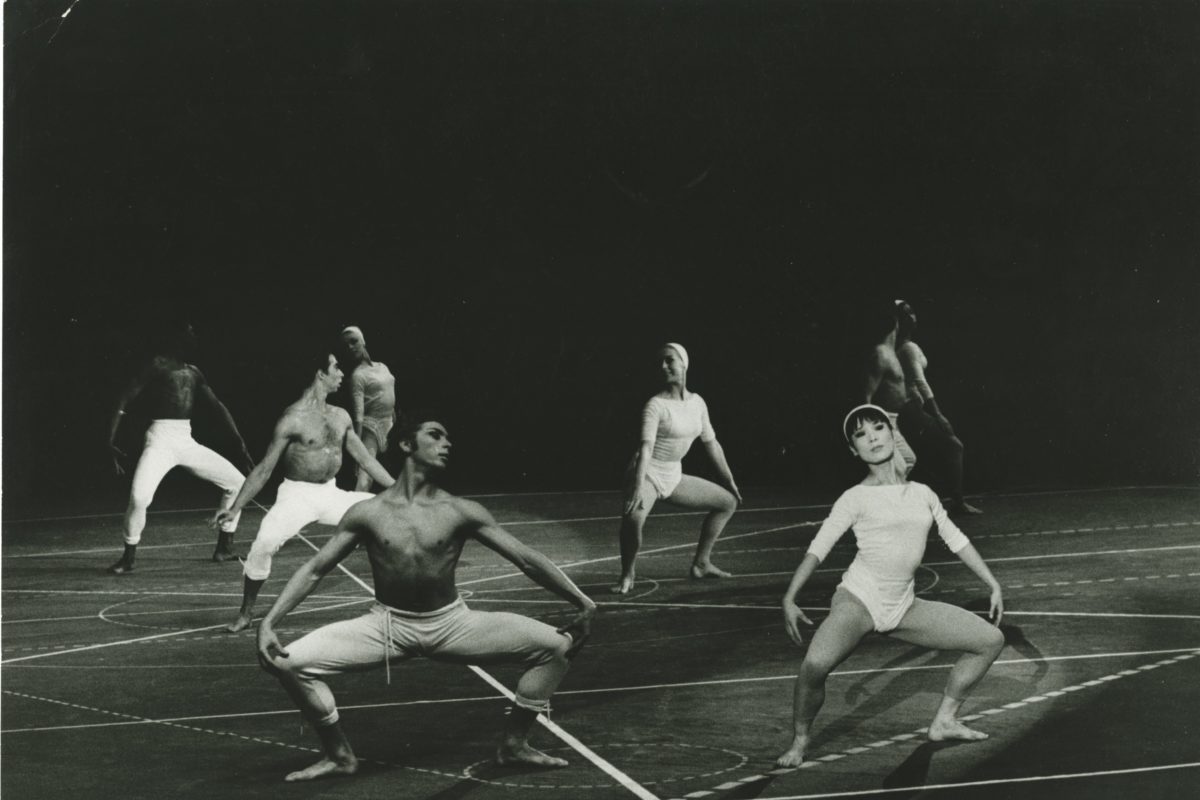

Thus begins the crazy and meticulous analysis of the score. He, who had not studied music, eventually dissected the complex architecture of the work and memorized it. He thematized each movement. The first would be the earth, the struggle to achieve an ideal. The second, the fire, the joy of dancing. The Adagio, water, love. And in the end, freedom, air. Like a chameleon, he ventures into hidden lands and lets himself be guided by wild notes and unpredictable choirs. He sketches steps and imagines group movements: a group of girls here, boys there, a few soloists in the center—with always in mind the idea of a ritual that calls for solidarity—a dance addressed to the community. May 68 is not that far removed. “In The Ninth there is dance, music, songs, theater,” he said in an interview. “It is written that it was a revolution, but I only went back to the roots. In the Greek tragedy, the ancient choir spoke, sang, and danced. The gender separation came later.”

Created in a round theater, the Cirque Royal in Bruxelles, The Ninth Symphony was danced by the Ballet of the 20th Century all over the world—from the superb Saint Mark’s Square in Venice to the Kremlin Palace, via the Verona Arena and Mexico City, during the 1968 Olympic Games—before being performed again at the Paris Opera, 18 years after its last performance in 1978. It is with a pirated video recorded at La Scala in Milan, that Maurice Béjart and Piotr Nardelli, his assistant at the time, rediscovered the gestures, emotion and original spirit of the ballet.

Teaser of dancing Beethoven – a documentary about The Ninth Symphony. (Production: Arantxa Aguirre, 2016). Available on bejart.ch/en/boutique

Tokyo premiere

In November 2014, fifty years after its creation, Gil Roman had the audacity to revisit this masterpiece and bring together 250 performers in Asia: a choir, musicians and two ballet corps that had never danced it before, the Béjart Ballet Lausanne and The Tokyo Ballet. Three years of work, travel and exchange to reclaim the original meaning, the 64’ ideal. He was helped by Piotr Nardelli, who went to Tokyo to transmit this masterful work to Japanese dancers. Piotr had danced this piece in the 1970s and assisted Béjart in the Ballet’s revival in 1996 at the Paris Opera.

Gil Roman had long dreamed of this sublime communion between dancers and musicians on stage. The Artistic Director is intimately familiar with Béjart’s work and for The Ninth, he gracefully transformed himself into a painter, a director and a passer. Without mannerism, he underlines what we might not be able to see: a hand, a look, a jump. As if each movement had to contain the passion of a final gesture. Nothing is left to chance.

A universal language

Maurice Béjart wanted to bring color to the poetic conversations of the performers on stage—brown, red and yellow. Excerpts from Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy resonate to the sound of Western and African Bongo percussions. For Béjart, dance is a universal language that can establish links between cultures. It has a sacred character appealing to occult forces. He uses physical expression and the Nietzschean thought to share a deeply intimate feeling. Béjart seeks the junction point between reality and transcendental concepts, between Apollonian and Dionysian. For him, dance and God, philosophy and dance, are one.

Thus, the dancers emerge from the most melancholic shadow, from darkness to light, to set the scene ablaze. They turn, run, lighten up, and seek the common breath that will allow them to continue. The light sparkles and radiates the space before everything flickers. The audience, captivated, lingers on a soloist’s step, breathing to the rhythm of an ensemble that is gradually being built. The costumes, wonderfully sober, highlight both the presence and absence of the body. With delicacy and passion, the performers seize the stage to transfigure it. They become icons. “Let’s dance like troubadours between saints and floozies, between the world and God. This is our dance!” Everything is transcended: music, dance, Humanity.

Sophie Grecuccio